Just back from a delightful couple of days in the north of England working through an extraordinary private collection of early British tourist and guide-books. My co-author Ashley Baynton-Williams and I are planning on an online supplement of addenda and corrigenda to our “British Map Engravers” and, although we have only been told of a mere handful of ‘missing names’ since it was published in 2011, we both felt that there must be more. We also felt that, if anywhere, we would probably find them amongst the numerous ad hoc maps locally produced for local guides. We jumped at the chance to get to work on this collection.

We were right in our assumption and shall now be adding entries for John Beck of Leamington; Joel Bennett of Southampton, for an attractive map made to accompany the fourth edition of John Bullar’s “A Companion in a Tour round Southampton” (1819); William Gill Brown of York for a couple of plans made to accompany a guide published by Henry Sotheran in York in 1852; James Chapman, also of York; the splendidly-named Appleyard Ginder of Canterbury; the York lithographers William Roger Goddard and his partner John William Lancaster; the well-known wood-engraver Orlando Jewitt, now to be included for a plan of Ripon Cathedral; John Lavars of Bristol; the artist Philip John Ouless of St. Helier and his collaborator H. Walter; that English pioneer of lithography David Redman, and possibly James Williamson of Lincoln, although strictly speaking he falls just outside our cut-off date. A dozen fresh names to add to the 1600 or 1700 already in the dictionary – a few more than we hoped, considerably less than we feared.

We saw many other delightful things of course – I was particularly taken with a plan of Cambridge by Friedrich Schenck of Edinburgh – a little jewel of early colour printing made to accompany “The Pictorial Guide to Cambridge” (1847) – but we always like to come across pictures of old bookshops and here is the frontispiece to “Adams’s Pocket London Guide Book”, published by W. J. Adams of Fleet Street – undated but evidently one of the spate of new London guides brought out to try and cash in on the Great Exhibition of 1851.

The text to the book is by the always interesting Edward Litt Leman Blanchard (1820-1889), king of pantomime, peerless and tireless hack – he who once wrote,

“Those that work are the illustrious,

And those most noble are the most industrious”.

The frontispiece is captioned “Fleet-Street and St. Dunstan’s West. – Mid-Day” (although the clock outside the watchmaker William Halksworth’s premises, next door to Adams, is very far from mid-day). It was engraved by ‘Delamotte’ –Freeman Gage Delamotte of Red Lion Square – a regular contributor to Adams’ publications, but it is the publisher William James Adams (1807-1873) himself who interests me. He is the almost wholly forgotten man behind the story of Bradshaw’s Railway Guides – those indispensible handbooks which so informed the travel and coloured the imagination of generations of British readers.

Michael Portillo has done it on television more recently, but here is Israel Zangwill planning his holidays in the 1890s – “I would travel for weeks in Bradshaw, and end by sticking a pin at random between the leaves as if it were a Bible, vowing to go where destiny pointed. Once the pin stuck at London, and so I had to stick there too, and was defrauded of my holiday”.

Michael Portillo has done it on television more recently, but here is Israel Zangwill planning his holidays in the 1890s – “I would travel for weeks in Bradshaw, and end by sticking a pin at random between the leaves as if it were a Bible, vowing to go where destiny pointed. Once the pin stuck at London, and so I had to stick there too, and was defrauded of my holiday”.

The Bradshaw was as ubiquitous and as necessary as the latest app. Andrew Lang complained in 1892 that the older families nowadays never added a book to their ancestral libraries, “except now and then a Bradshaw or a railway novel”. The Bradshaw turns up everywhere in fiction – in Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”, in Daphne du Maurier’s “Rebecca”, in Max Beerbohm’s “Zuleika Dobson” (one of the two books in Zuleika’s ‘library’) and in Erskine Childers’ “The Riddle of the Sands” – “an extraordinary book, Bradshaw, turned to from habit, even when least wanted, as men fondle guns and rods in the close season”. And they were loved most of all by the crime writers – to disprove an alibi, to project a theory, to hinge a plot. There are Bradshaws in the Sherlock Holmes stories, in Agatha Christie, and in all their lesser brethren. Here’s the conspiracy-obsessed William Le Queux in 1919 (I include this chiefly to please a friend):

“That gave me a further clue. I took down a Bradshaw, and, glancing at the train by which the little fat man had travelled, made an interesting discovery. It was the Newcastle express. I began to see why the mysterious little man had booked to Peterborough. That afternoon I ascertained that the parrot’s cage in the house in Lembridge Square sported a broad ribbon of yellow satin … An hour after midnight came another air-raid alarm – the second to coincide with the appearance of the yellow ribbon” (Sant of the Secret Service).

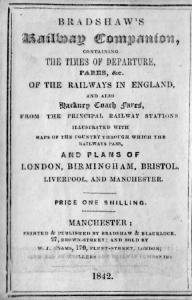

The Bradshaw was of course the invention of the eponymous Mancunian George Bradshaw (1800-1853), map-engraver turned publisher, and Bradshaw is rightly and duly honoured – but it was his London agent W. J. Adams of Fleet Street who was his chief apostle. It was at Adams’ transformative suggestion that the initial price was halved and that publication became monthly. It was Adams who soon became the lead publisher. It was Adams who commissioned Blanchard to compile a whole series of travel guides to lure people on to the trains and who more or less invented the concept of rail travel for pleasure – “Bradshaw’s Descriptive Guide to the London & Brighton Railway” (1844); “Bradshaw’s Descriptive Guide to the London & South Western Railway” (1845); “Bradshaw’s Descriptive Guide to the South Eastern Railway” (1846); “Adams’s Illustrated Descriptive Guide to the Watering-Places of England, and Companion to the Coast” (1848); “Adams’s Pocket Descriptive Guide to the Lake District” (1852) and so many more. As early as 1848 he published Edwin Lee’s “Continental Travel with an Appendix on the Influence of Climate, the Remedial Advantages of Traveling [sic]”.

Adams became even more of the guiding figure after Bradshaw’s untimely death (he died of cholera in Oslo in 1853) – and it was Adams who expanded the range of the Bradshaw companions, timetables, guides and separately published maps to cover the railways and cities of the world. And for light reading on the journey – Blanchard and Adams combined again to publish “The Carpet Bag, Crammed Full of Light Articles, for Shortening Long Faces and Long Journeys” (1852). It was Adams, in essence, who made the Bradshaw the national institution it became. The whole story of the Bradshaw phenomenon is there in the picture.

Adams became even more of the guiding figure after Bradshaw’s untimely death (he died of cholera in Oslo in 1853) – and it was Adams who expanded the range of the Bradshaw companions, timetables, guides and separately published maps to cover the railways and cities of the world. And for light reading on the journey – Blanchard and Adams combined again to publish “The Carpet Bag, Crammed Full of Light Articles, for Shortening Long Faces and Long Journeys” (1852). It was Adams, in essence, who made the Bradshaw the national institution it became. The whole story of the Bradshaw phenomenon is there in the picture.

As for William James Adams himself, little is known. The Wikipedia entry for George Bradshaw, although to some extent acknowledging Adams’ importance, still gets his name wrong (William Jones Adams). He was born in Westminster on 12th June 1807, the son of Thomas and Susanna Adams, and baptised at St. James Piccadilly. His early life beyond that remains wholly obscure. He married Sarah Hoole (1813?-1877), the daughter of an engineer, at All Saints Poplar 14th March 1831 and when their first child Henry John Adams (1831-1881) was baptised early in 1832, W. J. Adams was described simply as a mariner. Quite how he progressed from there to becoming Bradshaw’s London agent in 1841, initially at 170 Fleet Street and then from 1843 at 59 Fleet Street remains unknown.

As for William James Adams himself, little is known. The Wikipedia entry for George Bradshaw, although to some extent acknowledging Adams’ importance, still gets his name wrong (William Jones Adams). He was born in Westminster on 12th June 1807, the son of Thomas and Susanna Adams, and baptised at St. James Piccadilly. His early life beyond that remains wholly obscure. He married Sarah Hoole (1813?-1877), the daughter of an engineer, at All Saints Poplar 14th March 1831 and when their first child Henry John Adams (1831-1881) was baptised early in 1832, W. J. Adams was described simply as a mariner. Quite how he progressed from there to becoming Bradshaw’s London agent in 1841, initially at 170 Fleet Street and then from 1843 at 59 Fleet Street remains unknown.

One of his comparatively small number of non-railway specific publications was “Compendium of the Improvements Effected in Electric Telegraphs, by Messrs. Brett and Little, with a Description of their Patent Electro-Telegraphic Converser” (1847), which suggests he was a man entirely comfortable in the machine age. And he was a man obsessed with work, one of Blanchard’s “most industrious” – although when his children were small the family had homes in Poplar and then Newington, by the 1850s they were all living right there on the premises at 59 Fleet Street.

One of his comparatively small number of non-railway specific publications was “Compendium of the Improvements Effected in Electric Telegraphs, by Messrs. Brett and Little, with a Description of their Patent Electro-Telegraphic Converser” (1847), which suggests he was a man entirely comfortable in the machine age. And he was a man obsessed with work, one of Blanchard’s “most industrious” – although when his children were small the family had homes in Poplar and then Newington, by the 1850s they were all living right there on the premises at 59 Fleet Street.

The eldest son was trained in lithography and his younger brother William Robert Adams (1846-1917) was soon employed as his father’s assistant. Both became partners in or about 1868, when the firm became ‘W. J. Adams & Sons’. The only daughter, Catherine Sarah Adams (1844-1861), died tragically of consumption at the age of seventeen. Aside from his publishing, Adams was a famously efficient passport agent, able to produce a passport with all the necessary visas in next to no time. He became a freeman of the City of London in 1856 and he was also the senior churchwarden at St. Dunstan in the West, just across the street, in 1869. He died at 59 Fleet Street on 21st December 1873 and was buried at Norwood on the 27th, leaving a considerable estate valued at something under £9,000.

The business continued unchanged as ‘W. J. Adams & Sons’ at 59 Fleet Street beyond his own death and that of his elder son in 1881, until William Robert Adams retired to Dorking in 1901, the enterprise then reverting to the Blacklock family, Bradshaw’s original partners in Manchester. And at this point, the Bradshaw was still only halfway through its illustrious history – the guides continued appearing until 1961.

Thank you. Say, how in the world is it possible that “Pink Parade” by J.B. Booth (memoir of pre-WWI in England; published in America by Dutton in 1933), with the exception of Chapter 13, was so unreadable? And, may I ask, what did “J.B.” stand for? If you happen to know, please let me know.

LikeLike

It’s John Bennion Booth (1880-1961), but why Chapter 13 was suppressed in the American edition I have no idea.

LikeLike

Laurence:

You are most kind.

A misunderstanding has arisen: The book itself is, unfortunately, unreadable (well, at least for the first 77 pages, after which I employed the “mercy rule” and threw in the towel).

Having a lifelong interest in horse racing, in the process of pulping the book, I noticed that Chapter 13 dealt with the subject (among others) and found it quite readable.

Now, I somehow have given you the impression that the American version of Chapter 13 had been “suppressed.” it was not, and it is the only thing in the book I found worth saving, save the splendid Alfred Bryan caricatures of actors J.L. Toole & Henry Irving.

Eminently readable: Paul Johnson’s “Brief Lives” (2010), which somehow was published without a Table of Contents, and without an Index.

Again, thank you for your prompt and considerate response.

Don

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for all the research! My interest in Adams is that in 1862 he published ‘The Paper Makers’ and Stationers’ Calculator. Compiled by the amazingly-named Edmund Napoleon Haines. However the t/p shows Adams was then located in Pudding Lane, half a mile from Queenhithe, where ENH was in partnership with the celebrated papermaker T H Saunders

LikeLike