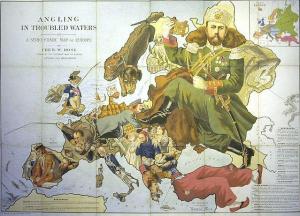

Fred W. Rose is of course widely known for his Victorian satirical caricature maps. Reproductions of his Serio-Comic War Map for the Year 1877, with its alarmingly tentacled Russian octopus, are nowadays one of the British Library’s best-selling lines. You may even recall Tim Bryars and myself talking about Rose on television in the BBC 4 Beauty of Maps series a few years ago (although this was mainly Tim, you would have to have been very wide-awake to catch my fleeting contribution). The maps have been subjected to considerable analysis elsewhere (see for example Tim’s The Avenger, not the Octopus: Fred Rose’s Other Map of 1877 piece from last year on his excellent Unto the Ends of the Earth blog).

Widely known for his work, certainly, but we search high and low for any information at all about Rose the man himself. I’ve rather lost count of the number of people who have asked me to come up with the biographical goods – Tim certainly, Marleen Smit, who was also in the television programme and has written and lectured on Rose, Ashley Baynton-Williams, who has likewise written about him – and quite a few others.

I have tried without success to answer the basic question of who Rose actually was on a number of occasions. The problem is that there were 232 Frederick Roses recorded in England and Wales on the 1881 Census returns (as well as sixteen Frederics, forty-one plain Freds, fifty-three half-hidden as Fredk, and four more in Scotland). Even removing those too young to have been producing maps by the 1870s, the possibilities are wide. None gives artist, illustrator or caricaturist as an occupation, but the sporadic and occasional nature of the known maps suggests that this was not a full-time occupation for Rose. There was no real basis for choosing one Fred Rose over another.

For some time I had my eye on Frederick William Rose (1848-1910) of Clerkenwell as the most likely candidate: aged thirty-three in 1881 and employed as a lithographic printer – correct middle initial, the right sort of age and certainly connected with printing if not with caricature. But there was a lack of any supporting evidence. It was right to be cautious. It was another Frederick William Rose altogether.

The Fox Hunter at Fault or a Scrambling Breakfast – a sketch by Thomas Rowlandson from the Rose Collection. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The answer, when it finally came, turned out, as so often happens, to have been hidden in plain sight all along. The Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum appears to have nothing at all by Rose in its collections. No point in pursuing him there, we thought – and yet there was, because what the Department does have is Rose’s own rather attractive personal collection of over 160 prints and drawings – drawings by Thomas Rowlandson, Constable, George Morland, James Duffield Harding, the Westalls, David Roberts and Walter Greaves, as well as etchings by William Strang and numerous studies by earlier masters, including Guercino, and even a Rembrandt sketch. The whole collection was presented to the Museum in 1943 by Rose’s eldest son, Eric Hamilton Rose. This followed the earlier gift of numerous Japanese prints, etc., from Rosamond Rose, Eric’s wife. The biographical notes attached to these bequests are cursory, but there is an address in Kensington for Fred W. Rose and the names of both his son and daughter-in-law – any one of which could and should long since have rapidly led to his identification.

In fact that is not where I found him. It was the chance discovery of a letter published in the Pall Mall Gazette on 19 August 1896 which eventually led to the right man. The letter, signed Fred W. Rose, made a witty complaint about the writer not having been allowed to take sketching materials into Kew Gardens on a Sunday, as painting was apparently not allowed in the Gardens on that day.

The letter proved the key, because it gave the Kensington address at 4 Cromwell Crescent – an address which soon led to Frederick William Rose (1850-1915), an almost exact contemporary as well as a namesake of the printer, but occupying a rather more exalted station in life. Born at Paddington and baptised at Holy Trinity on 3rd July 1850, this Frederick William Rose was the son of Major Hugh Munro St. Vincent Rose of Glastullich and Tarlogie (1800-1867), Twelfth Lancers, J.P., D.L., and landed proprietor, and his wife Frances Walrond Roberts (1819-1908), daughter of the Reverend Edward Roberts of Lyme Regis, who had married in 1836. [Correction: Although the baptism did not take place until July 1850, Rose was actually born on 12th November the previous year. The official registration of his birth has not been traced, but I am very grateful to Rod Barron (see postscript below) for pointing out the announcement in the Morning Chronicle (15 November 1849) to that effect]. Fred W. Rose spent his early years at 3 Park Place Gardens, Paddington, with his parents, three older siblings, a manservant, a lady’s maid, a nurse and a cook. The wider reaches of this prosperous Scottish family included Lachlan or Lauchlan Rose, the inventor of Rose’s Lime Cordial.

The Rose family subsequently moved to Thicket Road, Penge, where Fred Rose spent his boyhood. The Morning Post of Saturday 2nd November 1867 announced his appointment to a clerkship in the Legacy Duty Office at Somerset House, an office where he was to spend his entire working career, eventually rising to become Assistant Principal. At the age of twenty-one, on 27th June 1871, Rose married Catharine (Kate) Ross Gilchrist (1850-1932), second daughter of the late Daniel Gilchrist and his wife Jane Reoch, in a Highland wedding at her grand family home at Ospisdale House, near Dornoch, north of Inverness.

The young couple lived first at 9 Kensington Crescent, but by 1873 had moved to 4 Cromwell Crescent, where Fred W. Rose (as he generally signed himself) was to live for the remainder of his life. The house still stands and can be seen from the main road into London from Heathrow as you near Earl’s Court.

To judge from Rose’s handling of Disraeli and Gladstone in the Comic Map of the Political Situation in 1880, we might suppose (although it’s not entirely one-sided) that he was politically a Conservative. I assume he must be the Frederick W. Rose reported in the press as the chairman of the Holland Ward Conservative Association in Kensington in 1883-1885. Any lingering doubt on this score is removed by the disobliging references (perhaps surprising in a relatively senior civil servant) to both Joe Chamberlain and W. E. Gladstone in Rose’s Notes on a Tour in Spain (1885), published by the recently formed and rather obscure publishing house of T. Vickers Wood. The nature of other Vickers Wood publications suggests that this may have been a species of vanity publishing, although the book, dedicated to Rose’s mother, was positively reviewed in the Morning Post, whose reviewer found it “bright and unpretentious”.

Rose clearly liked to travel: he refers to earlier tours in France, Germany, Italy and elsewhere in Europe. He could evidently speak French and German and had taken the trouble to learn some basic Spanish and some Spanish history before setting out. He and his wife seem readily to fall in with and befriend other travellers of various nationalities. The leisurely tour took in Barcelona, Montserrat, Tarragona, Valencia, Cordova, Granada, Seville, Madrid, Toledo, Salamanca, Valladolid, San Sebastian and elsewhere. While it is interesting to discover that he thought a loaded revolver a necessary companion on a trip to nineteenth-century Spain and that he and his wife liked to collect bric-à-brac, the book is, on the whole, somewhat lightweight. Rose clearly shared many of the period prejudices and condescension of his race and class towards foreigners (unless aristocratic) and the lower orders in particular. He clearly had an eye for the ladies, although not an especially generous eye. There is rather too much on railway carriages, the price of railway tickets, hotels, exchange rates and petty triumphs in haggling, although his determined attempt not to prejudge bull-fighting and the subsequent fully detailed denunciation of it is to his credit. The intended humour is somewhat ponderous: his nocturnal experiences suggest to him that Burgos could usefully be spelt without the ‘r’ and the ‘o’. It is only when he discusses art that he really finds an original and knowledgeable voice, being prepared, for example, to depart from the accepted view of Goya. The book is illustrated with his own lively sketches which are perhaps its most enduring and attractive feature.

His wife hardly appears at all, only stepping into the foreground of the narrative on a couple of occasions: once when she appears in the evening wearing a shawl in ‘our’ tartan to the amusement of the other hotel guests, and once where she cleverly snubs a flirtatious, ‘impudent’ and ‘brazen-faced’ girl in a cigarette factory – a curious incident for Rose to think worth recording.

One way in which Rose wasn’t a typical specimen of the British traveller abroad was in his knowledge and appreciation of modern French literature, in particular Théophile Gautier and Émile Zola, both of whom he refers to with evident familiarity. Conservative in politics, but with an avant garde taste in novels, Rose’s next book was to be very different in tone. Written under the pseudonym ‘Martius’, His Last Passion : A Sensational and Realistic Story of English Modern Life (1888),[i] is of interest not least in being one of only a handful of publications from the short-lived Hansom Cab Publishing Company. The publishers somehow squandered the massive profits which they must have made through the outstanding success of Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab and soon went bankrupt, but they must have looked for similar success from Rose’s deliberately sensational novel. It certainly caused something of a furore. I haven’t read it, chiefly because I can’t lay my hands on a copy (the British Library copy has apparently been ‘mislaid’), but contemporary reviewers give us the gist:

“It is a novel which describes dangerous liaisons among married people in high life— where plots and counter-plots of illicit love and passion are mingled, and is sure to find many readers” (Wrexham Advertiser).

“It contains no murder, no mystery, but is a too faithful description what is almost ‘free love’ among a few members of the upper circles” (Burnley Gazette).

“To those who delight in the exposure of frailty among the upper ten, His Last Passion … will prove most fascinating reading. The characters are so natural that they would appear to be drawn from life, although there no trace of the fiction being founded on any well-known scandal. The author is evidently a Society man, and his descriptions of the interior of West End houses, and the manners of their occupants’ somewhat fast circles, are intensely graphic … It cannot be commended to the young” (Northampton Mercury).

“The plot abounds in love intrigues of a reprehensible character, and the borders of decency are all but overstepped” (Hampshire Telegraph).

“The author of His Last Passion admits that it may be objected against him that he has not depicted a single perfect character. He is only partly right. His characters might very fitly be described as perfect fiends … the parading of the details of three or four adulterous liaisons through the greater part of a book cannot be atoned for by the tacking on of so trite a moral at the end” (Aberdeen Journal).

“One of the most sensational, and at the same time one of the best stories we have read for a long time. The plot is exceedingly clever, the characters are all well drawn, and the incidents are grouped together in a way that shows both genius and skill on the part of the author” (Leeds Times).

“There is not one character pourtrayed by the writer that does not outrage our moral sense … If this be the first book written by Martius, let us hope, on public grounds, that it may the last” (Fife Herald).

Rose himself wrote, “From an ethical point of view, I know it would have been better to bring upon my characters a greater punishment than I have done. But I write for men and women of the world who know that comparatively few liaisons lead to a public scandal with all its bitter consequences”. They were words which were soon come back to haunt him.

On 5th April 1891, Census Night, Fred and Kate Rose were at home with their three sons (all educated at St. Paul’s), their cook, a housemaid and a lady’s maid. It was to be one of the family’s last evenings together: three weeks later, on 25th April, Rose filed for divorce, citing his wife’s adultery on 21st April 1891 at the Castle Hotel, Tunbridge Wells, “and on divers other occasions in March and April”. Scandal and bitter consequences. The divorce was not contested, but there was a dispute over the custody of the two younger sons. Quite why Rose chose publicly to humiliate his wife in this way – and humiliation it would have been in 1891 – is not known. Unless it is a purely middle-class view of the gentlemanly thing to do, the done thing was for the husband always to accept the blame in such circumstances.

He must have been very angry indeed and it may in part have to do with the identity of the other man – Arthur George Witherby (1856-1937) – Oxford educated, trained for the law, journalist, editor and himself a gifted caricaturist, best known as ‘Wag’ of Vanity Fair, a magazine he later came to own. Leslie Ward (Spy), the magazine’s best known illustrator, remembered him as “a very clever caricaturist and draughtsman, but he is equally clever as a writer; in addition to which he is a good sort and keen sportsman”. Fred Rose probably didn’t quite see it that way. Witherby married Kate in 1894. She appears to have lived much abroad and died in France in 1932.

Rose’s second novel, I Will Repay, appeared in 1892, dedicated to Tolstoy in tribute, and published under his own name by another short-lived publishing house (another which specialised in avowedly modern fiction) – Eden, Remington & Co. It was as controversial as its predecessor – a novel based on the Jack the Ripper murders and an exploration of ‘epileptic mania’. Removed from Whitechapel to Rose’s more familiar and more fashionable side of town, the book is a serious early attempt at understanding the making and psychology of a serial killer. Prefaced by an admission that his earlier novel should have expressed ‘more emphatically my own personal disapproval’ of adultery, it is an uncomfortable read. In particular, it is difficult not to guess at a portrayal of his former wife in his description of a somewhat vacuous woman married to a dry old stick, a fading beauty of a certain age, who toys with the idea of a liaison with the killer.

There is an interesting passage, obviously drawn from personal experience, describing the pleasures of being a pseudonymous author and hearing your work discussed by people who have no idea that the author is present in the room. And there is a fascinating account, again probably drawn from personal experience, of a very bohemian party hosted by the secret mistress of the killer’s father. The reviews again were mixed, but they were smaller in number and the tone mainly negative. Although Rose returned to making his caricature maps, he never wrote another book.

In tandem with his career in the Civil Service, Rose had been active in company promotion – his name was prominent, for example, in the formation of the Civil Service & General Bread & Flour Supply Association in 1879. He retired in his fifties, and took up various directorships. At the time of his death he was a director of the Canadian Mining Corporation, the Casey Cobalt Mining Company, and other cobalt enterprises.

His eldest son, Frederick (later simply Eric) Hamilton Rose (1872-1947), who donated the collection to the British Museum, went into the City, married well, made a fortune, lived at Wytham Abbey near Oxford and subsequently bought Leweston Manor near Sherborne in Dorset, where he bred Guernsey cattle and collected violins. Rose’s only daughter, Muriel Hope Rose (1873-1940), was still living at Cromwell Crescent at the time of her death. The two younger sons followed their grandfather and two uncles into careers in the army. They were among the seasoned troops sent immediately into the fray when the Great War broke out – and among the first to die. Captain Ronald Hugh Walrond Rose (1880-1914) was killed in action in October 1914, posthumously mentioned in despatches by Field Marshal Sir John French, while his elder brother, Major Launcelot St. Vincent Rose (1875-1914), was killed in action the following month at Fleurbaix. They are commemorated in twin memorial stained glass windows erected by their mother in Creich Parish Church at Bonar Bridge, while Ronald Rose’s moving diary of the early months of the war is now heavily featured on the Dornoch Historylinks website.

His eldest son, Frederick (later simply Eric) Hamilton Rose (1872-1947), who donated the collection to the British Museum, went into the City, married well, made a fortune, lived at Wytham Abbey near Oxford and subsequently bought Leweston Manor near Sherborne in Dorset, where he bred Guernsey cattle and collected violins. Rose’s only daughter, Muriel Hope Rose (1873-1940), was still living at Cromwell Crescent at the time of her death. The two younger sons followed their grandfather and two uncles into careers in the army. They were among the seasoned troops sent immediately into the fray when the Great War broke out – and among the first to die. Captain Ronald Hugh Walrond Rose (1880-1914) was killed in action in October 1914, posthumously mentioned in despatches by Field Marshal Sir John French, while his elder brother, Major Launcelot St. Vincent Rose (1875-1914), was killed in action the following month at Fleurbaix. They are commemorated in twin memorial stained glass windows erected by their mother in Creich Parish Church at Bonar Bridge, while Ronald Rose’s moving diary of the early months of the war is now heavily featured on the Dornoch Historylinks website.

It was the final bitter twist of Rose’s life – that a man who had made so light of the interplay of the Great Powers in his caricature maps should immediately lose two sons when the game ended and Europe began to unravel. He himself died a few weeks later on 3rd January 1915.

Postscript (19th December 2014): Excellent news. The map dealer Roderick M. Barron ( www.barron.co.uk), who specialises in satirical maps, tells me that he is working on a book on Rose and has a great deal more fascinating material about him than the basic facts given above. (He also has a copy of His Last Passion and all of the known maps). Over to Rod to fill us all in on the rest.

Pingback: Rusia, la (más) mala de la película en los mapas satíricos | Geografía Infinita

Pingback: William Bellinger Northrop (1871-1929) | The Bookhunter on Safari