This began as a gentle enquiry into the origins of Walter James Leighton (1850-1917), who became president of the ABA in 1909 – I’ll write more of him elsewhere, except to note that he was baptised at St. James Piccadilly, just across the road from the present ABA office, in August 1850. He was born into the London book trade, of course – but this set me thinking about just how many book-trade Leightons there were in mid-nineteenth-century London – and how so very important they were to the whole look and feel of the book at that time.

It’s not an excessively common name, but the London book trade either side of 1850 suffered from almost a surfeit of Leightons – three of them deemed worthy of an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, at least three others inexplicably not – there are some leviathans of the trade here. The “Post Office Directory” for 1855 lists Archibald Leighton & Sons of Lower Ashby Street, Northampton Square, bookbinders and cabinet-makers’ gilders; John and James Leighton, bookbinders and booksellers, of 40 Brewer Street, Golden Square; Leighton, Son & Hodge, bookbinders, of 13 Shoe Lane; Leighton Brothers, “chromatic printers”, of 4 Red Lion Square; Henry Leighton, wood engraver, also at 40 Brewer Street, with a further private address at 8 Lidlington Place, Harrington Square, and John Leighton junior, artist, giving the same addresses as Henry Leighton.

The last of these names is the most famous of all: this is John Leighton (1822-1912), also known as “Luke Limner”, the artist and bookbinding designer, whose stunning work can be found in Ruari McLean’s “Victorian Publishers’ Book-Bindings” (1974) and nowadays all over the internet (see for example the British Library Database of Bookbindings). But the question arises of how he might tie in with all the other Leightons.

Taking the names in turn, that of Archibald Leighton is particularly problematic – there were at least four bookbinders of this name working in London, some of their careers overlapping – potential for muddle in interpreting the standard authorities, Howe, Ramsden and Packer, even with the aid of further research in land tax records, census returns, insurance records and the like. Virtually the whole clan of London Leightons are suggested by an old article in “The Bookbinder” to have been descendants of the first of these, Archibald Leighton, a Scottish bookbinder, originally from Aberdeen, who settled in Coldbath Square, Clerkenwell, in or about 1764 – reputedly the father of twenty-three children by his two successive Scottish wives, Margaret Mudie and Euphan Douglas. He is believed to have died in 1799 and his widow, Euphan Leighton (d.1841), continued the business, initially in partnership with a stepson, George Leighton – a partnership formally dissolved in 1808, although Euphan Leighton remained the ratepayer in Coldbath Square until 1823. She then joined her own son, also Archibald, in Exmouth Street and they continued the business, latterly in partnership with Thomas Robert Eeles, until both Leightons died within months of each other in 1841.

The Archibald Leighton of Lower Ashby Street above was born locally in about 1793. He appears to have been the son and successor of George Leighton, and hence a grandson of the founder. He remained in Lower Ashby Street until his death in 1881. He and his Scottish wife, Harriet Gordon Ross, who married in 1814, had a number of children, evidently including the sons of Archibald Leighton & Sons above, one of whom was a fourth Archibald Leighton.

The Exmouth Street Archibald Leighton (1784-1841), son of Archibald and Euphan, is perhaps of more significance. He is claimed to have been the first bookbinder to produce trade bindings in cloth and the first to introduce gilt blocking on them (a process invented by his finisher, John Young) – no small claim in the history of the book production. There is at least one prior claim and it is a debate I hesitate to enter, but Arthur Chick deemed it substantially correct – at least in the commercial sense – in his “Towards Today’s Book” (1997). Archibald Leighton never patented the processes: a Sandemanian, he believed the free exchange of knowledge and ideas, but after his death in 1841 the business was continued by his widow,  Jane Leighton, born Jane Kemp in Exeter in about 1785 and clearly a woman of outstanding enterprise and determination – an unsung heroine of this story. Under her, the firm had re-settled in Shoe Lane by 1848, soon becoming the well-known Leighton, Son & Hodge partnership, with her son, Robert Leighton (1822-1888) and Frederick Hodge. Hodge left the partnership as early as 1853 (although a William Hodge was later involved), but the name remained unchanged throughout the ensuing decades, employing 300 workpeople by 1861 – the leading suppliers of the exotically blocked cloth gilt case-bindings of the period. Jane Leighton, still proudly calling herself a bookbinder aged sixty-five on the 1851 Census (although moderating this to gentlewoman in 1861), died in 1869 – but the firm kept on growing, the workforce reaching 400 by 1881.

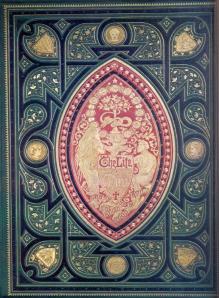

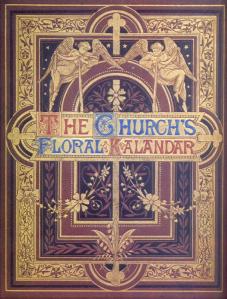

Jane Leighton, born Jane Kemp in Exeter in about 1785 and clearly a woman of outstanding enterprise and determination – an unsung heroine of this story. Under her, the firm had re-settled in Shoe Lane by 1848, soon becoming the well-known Leighton, Son & Hodge partnership, with her son, Robert Leighton (1822-1888) and Frederick Hodge. Hodge left the partnership as early as 1853 (although a William Hodge was later involved), but the name remained unchanged throughout the ensuing decades, employing 300 workpeople by 1861 – the leading suppliers of the exotically blocked cloth gilt case-bindings of the period. Jane Leighton, still proudly calling herself a bookbinder aged sixty-five on the 1851 Census (although moderating this to gentlewoman in 1861), died in 1869 – but the firm kept on growing, the workforce reaching 400 by 1881.  The work, often elaborate, often striking, standing out even in that great age of cloth gilt bindings, can still readily be found, both in bookshops and on the internet. A whole field of collecting in itself (and I find half a dozen examples readily to hand on my own shelves).

The work, often elaborate, often striking, standing out even in that great age of cloth gilt bindings, can still readily be found, both in bookshops and on the internet. A whole field of collecting in itself (and I find half a dozen examples readily to hand on my own shelves).

Leighton, Son & Hodge often utilised the designs of John Leighton (as did virtually all their competitors). John Leighton was born in Westminster, the son of another John Leighton (1800-1883), a bookbinder born in Clerkenwell, and his wife, Sarah Baynes (1799-1877), daughter of the artist James Baynes. The father was in turn the son of another John Leighton (1776?-1857), also a bookbinder, and his wife Eleanor Mann (d.1850), who married at Marylebone in 1797. And this first John Leighton is quite plausibly said to have been a son of the original Archibald Leighton, although the census return of 1851 records him as having been born in Scotland: the two facts are, of course, not wholly incompatible. This is the John Leighton who founded the Brewer Street firm above – he had been in Brewer Street since at least 1819 and was still there in 1851, although now recently widowed and retired. The head of the household in Brewer Street was now his other son, James Leighton (1802-1890), father of the future ABA president, and also born in Clerkenwell. It is not entirely clear (at least to me) whether the style John & James Leighton, which replaced the earlier form John Leighton & Sons in about 1850, refers to father and son or the two brothers. The second John Leighton, father of the artist, had been working independently as a bookbinder, bookseller and stationer at an address on Camden High Street – the artist as a young man was recorded at that address in both 1841 and 1851, but may well have come back into the family business on the retirement of his father. They were, of course, among the finest of fine hand-binders of the period – again often using designs from John Leighton the artist. Barring a brief interlude in the 1880s, when the style James & Walter James Leighton was used, the firm, which came in latter years increasingly to concentrate on selling antiquarian books, was known as J. & J. Leighton right up to the time of its eventual closure in 1937. Henry Leighton (1830-1882), an engraver who suffered from near-sightedness, was brother to the artist and his presence in Brewer Street, which the family occupied for about a hundred years, is readily explained.

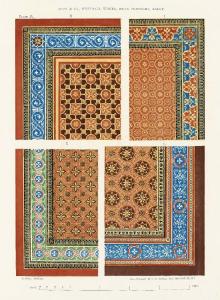

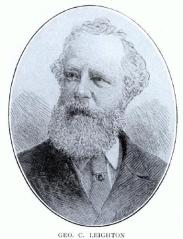

Leighton Brothers, the “chromatic printers”, were yet another highly important firm and, as the description suggests, pioneers of colour printing. One of the brothers, George Cargill Leighton (1826-1895) trained under George Baxter himself, but went on to develop faster and more economical methods of colour printing using wooden rather than metal blocks. In 1855, the firm were given the task of producing a special coloured Christmas Supplement for “The Illustrated London News” and, as Bamber Gascoigne noted, “It was the launch of coloured journalism”. By 1861 they were employing some eighty men and fifty boys.

George Cargill Leighton himself took over publication of “The Illustrated London News” and the firm’s colour work for books and magazines gave yet another fresh impetus to the look and feel of the nineteenth-century book. Another whole field of collecting there. The other brothers were Charles Blair Leighton (1823-1855), better remembered as an artist, and Stephen Leighton (1834-1920), the master printer. All three were sons of Stephen Leighton (1797-1881) and his Scottish wife Helen Blair (1796?-1870). And this Stephen Leighton, born in Clerkenwell, himself a master printer, is quite plausibly said to have been a son of George Leighton and a grandson of the original Archibald Leighton.

I’d like to have a touch more certainty on some of the earlier pre-census genealogy – sounds almost too good to be true – but quite a family, one way and another.