Another crowd-pleaser of an exhibition at the British Library: 250 years since the publication of Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, so a convenient enough excuse, as if one were needed, to celebrate 250 years of the gothic imagination, not just in literature, but in art, architecture, film, fashion and music.

Horace Walpole. Portrait by John Giles Eccardt, 1754. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Horace Walpole in 1754 with his hand on a volume from his library and the Gothicised Strawberry Hill in the background.

The first edition of Otranto, although dated 1765, appeared late in 1764. It was only with the second edition that Walpole admitted his authorship and the “gothic story” sub-title was added. Despite his own verdict that the novel was “fit for nothing but the age in which it was written”, nothing was ever quite the same again. As the exhibition swoops through time, place, mystery and the macabre, from Walpole through to Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight Saga, this is a powerful reminder of just how much of our mental furniture derives directly from the tradition Walpole brought into being. Packed together in the variously themed segments of the exhibition are William Blake, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, Charles Dickens, the Brontës, Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, M. R. James, Mervyn Peake, Angela Carter and Neil Gaiman and a host of others of greater or lesser celebrity.

The lead curator, Tim Pye of the British Library, gothically bearded and fresh from his recent stint on the faculty of the York Antiquarian Book Seminar, stepped forward to give us a little context. Walpole’s initial claim that the story was a translation from the sixteenth-century Italian manuscript of one Onuphrio Muralto (the manuscript recently rediscovered in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England) in fact should have placed it squarely in the context of that eighteenth-century vogue for literary fakery – the poems of ‘Ossian’ and the mediaeval concoctions of the marvellous boy, Thomas Chatterton.

The lead curator, Tim Pye of the British Library, gothically bearded and fresh from his recent stint on the faculty of the York Antiquarian Book Seminar, stepped forward to give us a little context. Walpole’s initial claim that the story was a translation from the sixteenth-century Italian manuscript of one Onuphrio Muralto (the manuscript recently rediscovered in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England) in fact should have placed it squarely in the context of that eighteenth-century vogue for literary fakery – the poems of ‘Ossian’ and the mediaeval concoctions of the marvellous boy, Thomas Chatterton.

But Walpole soon came clean and admitted that the book was the result of a lurid dream in the summer of 1764 and a subsequent eight weeks of intensive writing. He was of course a man who not just wrote ‘gothic’ but lived ‘gothic’ in his fantasy house at Strawberry Hill: a particular eighteenth-century take on ‘living the dream’.

Nothing begins in isolation and Walpole saw himself as harking back to mediaeval romance, chivalry and Shakespeare, and the exhibition commences with a nod to those. To my mind, the Jacobean revenge tragedies seem more direct precursors, but no mention made and this would depend on to what extent these might have been were available or known to Walpole. One of a number of unanswered questions that are still rattling around my head – always the sign of a good exhibition.

Much more to see: a proof copy of Walpole’s own Hieroglyphic Tales (1785) – wilder even than Otranto and only six copies published of the original edition; the second novel with a ‘gothic’ sub-title, Clara Reeve’s The Old English Baron (1778), “the literary offspring of The Castle of Otranto, written upon the same plan, with a design to unite the most attractive and interesting circumstances of the ancient romance and modern novel”; William Beckford’s Vathek of course; Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), etc.; Matthew Lewis, The Monk (1796). A claim was made that by 1800 a third of all the novels being published in England were in some sense ‘gothic’ (another question to quiz and ponder). Certainly there were enough for parody to set in: I think my favourite exhibit was the display case containing all seven of the “horrid novels” recommended to Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey.

The Nightmare, after Henry Fuseli. Print made by Thomas Burke. London, 1783. © Trustees of the British Museum.

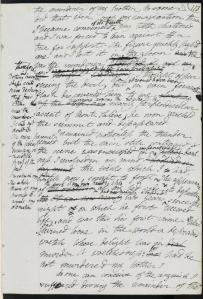

Echoes in the art of the period too – the whole theory of the ‘sublime’, romantic landscapes to inspire awe and wonder, and the fevered imaginings of Henry Fuseli. Back to literature and the seminal publications emanating from those evenings at the Villa Diodati: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) – wonderfully represented here by pages of the manuscript with Percy Bysshe Shelley’s hand-written comments in the margins (in the crowd at the press-view I couldn’t quite get close enough to see what he had written – more questions to answer) – and John William Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819).

Mary Shelley, manuscript of Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus © The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

From there to the terror of the soul of Edgar Allan Poe and then a move into more contemporary and more domestic horror: what is seen as the respectable gothic of the Brontës; the cramped and extraordinary manuscript of Wilkie Collins’ Basil: A Story of Modern Life (1852); the gothic elements in Dickens.

Back to vampires with the predatory female protagonist of Sheridan le Fanu’s novella Carmilla, first published in The Dark Blue (1871-1872), and the source of numerous film adaptations in multiple languages, not all of them in the best of all possible taste. It had never occurred to me before that Gustave Doré’s illustrations to Blanchard Jerrold’s London : A Pilgrimage (1872) were less stark social realism than an imaginative excursion into gothic menace, but so they are and rightly appear in this context.

‘Dear Boss’ letter from Jack the Ripper. Letter to the Central News Agency, September 1888. © The National Archives.

Quite the most blood-curdling exhibit in the entire exhibition is the blood-red ink of the (apparently genuine) ‘Dear Boss’ letter written by Jack the Ripper, a chilling moment where the horror of the imagination tumbles over the abyss into real life.

On to the high Victorian – the penny-dreadfuls, Jekyll & Hyde, Dorian Gray, and a whole room devoted to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), with even a vampire-slaying kit loaned from the Royal Armouries, ostensibly nineteenth-century (although there appears to be no substantiated record of such things prior to the Hammer Films era).

The curator’s tour was by now being led by Tanya Kirk, having difficulty in making herself heard over the competing sound-tracks of the numerous movie clips as we moved forward into the twentieth century and beyond. She made the undeniable point that the march of science had done nothing to dampen down the appetite for gothic – the films made the point quite loudly enough. We were introduced to themes of haunting, the menace of landscape, and the potential darkness of the animal world (think Hound of the Baskervilles, think Hitchcock’s The Birds, based on the Daphne du Maurier novel).

Daphne du Maurier featured again with a first edition of Rebecca (1938), as did John Buchan with Witch Wood (1927), but beyond that I couldn’t but feel that the literary element for the twentieth century was a little thin – the names lacking the resonance of their eighteenth and nineteenth-century counterparts. But then the film heritage is rich enough, from Nosferatu through to the most recent zombie thrillers. A suggestion seemed to be made that the zombie was a new concept for the twentieth century, a notion first introduced to popular culture by the American traveller and writer William Seabrook in his The Magic Island (1929). I’m not at all sure this can be right (whatever it may say on Wikipedia)– didn’t Robert Southey write about the ‘zombi’ over a hundred years earlier? Actually, didn’t he even have a cat called The Zombi?

Daphne du Maurier featured again with a first edition of Rebecca (1938), as did John Buchan with Witch Wood (1927), but beyond that I couldn’t but feel that the literary element for the twentieth century was a little thin – the names lacking the resonance of their eighteenth and nineteenth-century counterparts. But then the film heritage is rich enough, from Nosferatu through to the most recent zombie thrillers. A suggestion seemed to be made that the zombie was a new concept for the twentieth century, a notion first introduced to popular culture by the American traveller and writer William Seabrook in his The Magic Island (1929). I’m not at all sure this can be right (whatever it may say on Wikipedia)– didn’t Robert Southey write about the ‘zombi’ over a hundred years earlier? Actually, didn’t he even have a cat called The Zombi?

No matter – but I was little surprised not to see any Dennis Wheatley at about this point. He was a true guardian of the gothic flame. I was also surprised not to see any science fiction, which has always seemed to me to be the apotheosis of terror and wonder in the imaginative writing of the twentieth century – even if not always as explicit as in Vampires of Venus (which isn’t in the exhibition). But is there anything more gothic in spirit than Ray Bradbury? The very last thing I looked at was a Twilight Saga themed edition of Wuthering Heights. I felt at that point that I’d seen quite enough.

No matter – but I was little surprised not to see any Dennis Wheatley at about this point. He was a true guardian of the gothic flame. I was also surprised not to see any science fiction, which has always seemed to me to be the apotheosis of terror and wonder in the imaginative writing of the twentieth century – even if not always as explicit as in Vampires of Venus (which isn’t in the exhibition). But is there anything more gothic in spirit than Ray Bradbury? The very last thing I looked at was a Twilight Saga themed edition of Wuthering Heights. I felt at that point that I’d seen quite enough.

The British Library does this sort of thing very well – the exhibition will be a huge success and you should certainly make a point of seeing it. It ties together previously unrelated strands of thought and opens up any number of questions. There is a full programme of related events – and we can all look forward to a parallel gothic season on the BBC.

Don’t mistake me. I thoroughly enjoyed it and I’m sure you will too. And yet, and yet – there are things which still trouble me. There are parts of this exhibition trying all too desperately hard to be populist and ‘relevant’. What’s the Alexander McQueen frock all about? Is the Library now measuring itself solely by its success as a tourist attraction rather than the preservation of its intrinsic value as the deepest well of our national memory – our greatest research resource? I begin to fear so. It troubles me that the reception desk is now labelled ‘Box Office’. It troubles me that “a brand new Gothic-inspired product range has also been developed, available in the British Library shop”.

Travelling library of Sir Julius Caesar from Strawberry Hill, acquired in 1757 by Horace Walpole. Photography courtesy of British Library.

No real harm in any of this and I don’t mind too much, but I can remember a time when the Library bookshop was stocked with works of dense scholarship not findable elsewhere, rather than gift-books and picture-books. I can remember a time when the British Library was run by scholars for scholars (and there were undeniably weaknesses in that arrangement) rather than, as it now so often seems, by marketing men. Is it true that the surviving scholar-curators are becoming marginalised? Are they now valued more for their public relations skills than their scholarship?

Film still of Elsa Lanchester and Boris Karloff in The Bride of Frankenstein, 1939 © Universal / The Kobal Collection.

Has it become an institution in danger of forgetting what it’s for – that it’s about research and scholarship not show-biz? I hope not, I really hope not – but I fear these blockbuster exhibitions, however excellent in themselves, may yet turn out to be masking some uncomfortable truths behind the scenes.

Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination runs from 3 October 2014 to 20 January 2015 – http://www.bl.uk/whatson/exhibitions/gothic/index.html.

Reblogged this on Bibliodeviancy and commented:

Was lucky enough to attend this exhibition last night…quite the most splendid thing I’ve seen in ages…I thoroughly recommend it to anyone.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Shelf Fulfillment.

LikeLike